The mountains of the Transkei darkened under a swift-moving mist, swallowing horizon and hill with unnerving speed. This was once a semi-autonomous homeland—an apartheid creation roughly the size of Denmark—where Xhosa-speaking people were exiled in 1959 – many stripped of their South African citizenship anywhere in the country. It is the longest and most thorough suppression of human spirit which finally ended with Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990.

By half past five, the narrow, potholed road merged into the evening sky, dissolving the line between earth and cloud. Shapes emerged like ghosts through vapour—children on their way home, goats, cattle, dogs, horses. Animals stood adrift in the grey, drawn to the tarmac as the rain softened and cooled the porous soil on the sides of the road. The drive to the village of Coffee Bay is worse than I had been forewarned. The village is so remote that reputable travel guides don’t even mention it. Yet, it is the home of the crown jewel of the Wild Coast: Hole in the Wall.

Villages pressed close to the road. What little traffic there was had disappeared, leaving us the lone car for miles at a time. Speed bumps erupted from the surface without warning—some marked by reflectors, some not. In many stretches, the white lines simply vanished, and the only guide was the faint grass edging the road.

By seven-thirty, the fog had devoured the landscape entirely. All past cautions—friends, guidebooks, roadside warnings—echoed through my mind: Never drive through the Transkei after dark. Yet here I was, pulse quickening, breath deepening in a vain attempt to be calm.

The Transkei remains one of South Africa’s poorest regions. Decades of dispossession, unemployment, and marginal development have left deep wounds—addiction to welfare funds, alcohol abuse, narcotics made from crude meth precursors, petty crime and violence. The convenience stores are run by Somalis, Ethiopians and South African Indians charging high prices for tiny increments of goods, and the few rudimentary ‘resorts’ catering to backpackers and surfers are largely run by whites. Scattered among the impoverished valley is a minority of a white underclass from East London—the beginning of the Wild Coast—people who, as locals wryly note, “never prospered even in the days of white privilege.”

The fog grew thicker as the night turned black when Melanie, the proprietor of the self serve rental called and said emphatically, “Send me your location so I can track you. Don’t stop anywhere.” We inched forward at less than ten kilometres an hour till we arrived at her door, where her neighbour, Lindie – who owned a nearby restaurant- let us in. “I’ll have dinner in a few minutes. Melanie told me you haven’t eaten.” and disappeared into the row of hedges.

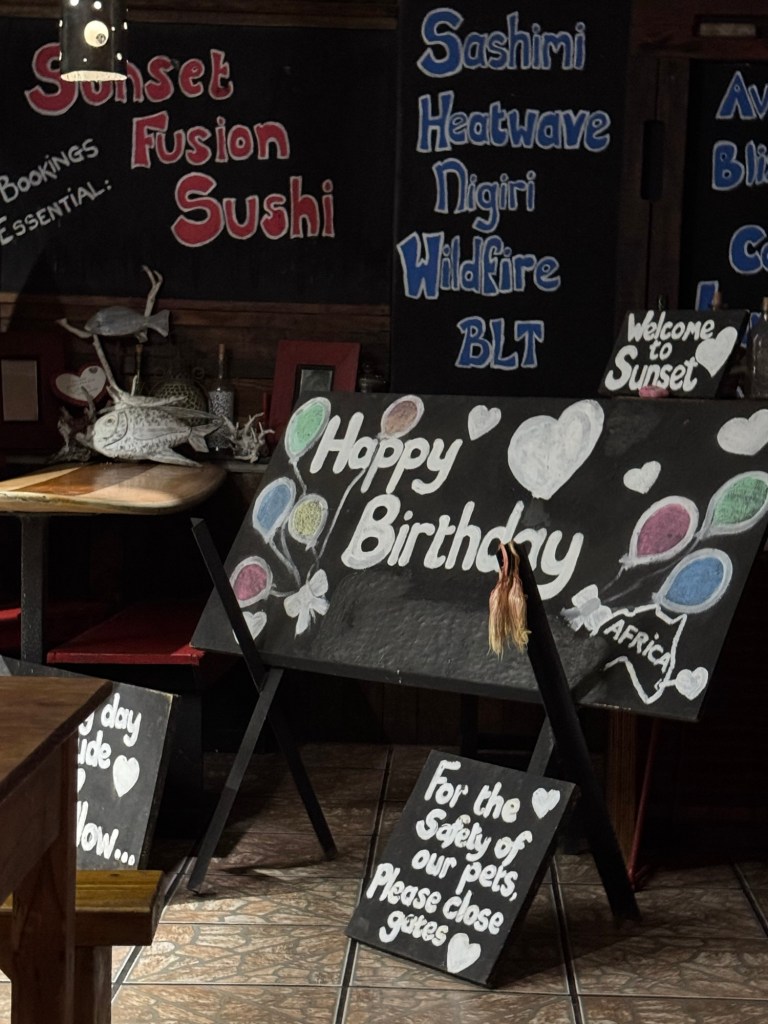

Lindie runs the restaurant almost entirely on her own; her last partner, she notes with a wry half-smile, absconded with a local, black prostitute. She presides over an improbably extensive menu—sushi to hamburgers, curries to grilled fish—all made painstakingly by hand. Her companions are a tail-less parrot that occasionally offers a “hello” and mimics an alarm, five dogs (only one of them friendly), four cats, a 130-kilogram pig called Pipsqueak that she raised from a runt, and a shy son who lives nearby. Her warmth and delight in cooking are matched only by her passion to tell her story: a childhood sketched in dysfunction, steadied by a stern grandfather who drilled survival into her bones, softened by remarkable moments of grace.

It would be easy, at first glance, to dismiss the menu after a look at her chaotic kitchen. Yet the few clients who find their way here are rewarded with food of startling finesse: chicken seared in a wok with garlic and fresh curry leaves, rice lightly fried with mushrooms, lentils and vegetables, fish dusted in maize meal and fried just to the point of crispness without a trace of oil.

Outside, Coffee Bay sleeps, save for the closed-door bars and the darker rooms where meth, cheap spirits and cash still move. Traditional rondavels, their round forms capped with tin or thatch, stud the steep hillsides, amidst small brick houses fronted by grandiose Roman columns. Free-ranging dogs, cattle, donkeys, goats, and pigs largely quiet. The roads are a patchwork—here gravel, there a sudden slice of concrete. The lodges catering to the youthful backpack and surfer mimic the rondavel cabins in form only.

In the morning, idle young men gather near the fence to offer unsolicited guiding services for the one-kilometre walk to Hole in the Wall. If you decline the tour, oysters, crayfish and beadwork are on offer; if those fail to tempt, requests for a few coins follow. The path itself threads into a small, mythic world: a Milkwood forest of twisted trunks and low, listening branches, hills rolling away in layers, and the steady, hollow thump of surf blasting through the ‘Hole in the Wall’ arch. At the Boiling Point, opposing waves collide and rear up in a foaming, shuddering crescendo.

Yet for all the drama of sea and stone, it is the laughter of children that endures, their bodies flying from the banks into the Mpako River as it laps quietly into the sea. Indifferent, two tourists in the distance pause to take photographs of the Hole In The Wall for a moment and leave, sadly oblivious to the greatest gift of nature – the laughter and unbridled joy downriver behind their backs.

In a region still marked by the most ruthless social engineering of the twentieth century, Transkei’s black citizens live with barriers to economic success that remain almost impossible to scale. Yet the unselfconscious joy of children in a clean river, unbothered by markets, forecasts or strategic plans, complicates the usual calculus of wealth and progress. As powerful nations sketch new blueprints for the movement of capital, manpower, and markets, the sound of those peals of laughter over clear water will unlikely enter into anyone’s analysis—yet it may be the one thing here that is wealth beyond measure.

To find oneself in Transkei at all is to be a bold explorer. Plainly you love to roll the dice.

My ignorance of the place was total so a bit of reading revealed a land of remarkable instability unlike anything in North America. Not only has the government frequently changed, the very forms of government have often shifted since the late 19th century through the 21st.

In spite of the fluxing of political structures, or perhaps because of it, the play of children, the persistence of old patterns and communities go on with a reliable permanence. Distant enemies of the land’s peace may plot the “Bright Future” of such a place. They hope for a disrupting catastrophe so that the customary traditions of land tenure collapse and they may redevelop such place as a playground for the bored tourists a decade later.

So far Transkei seems safe in it’s modest precariousness and humanity.

Hopefully you will follow suit in your travels.

Best Regards DM

LikeLike