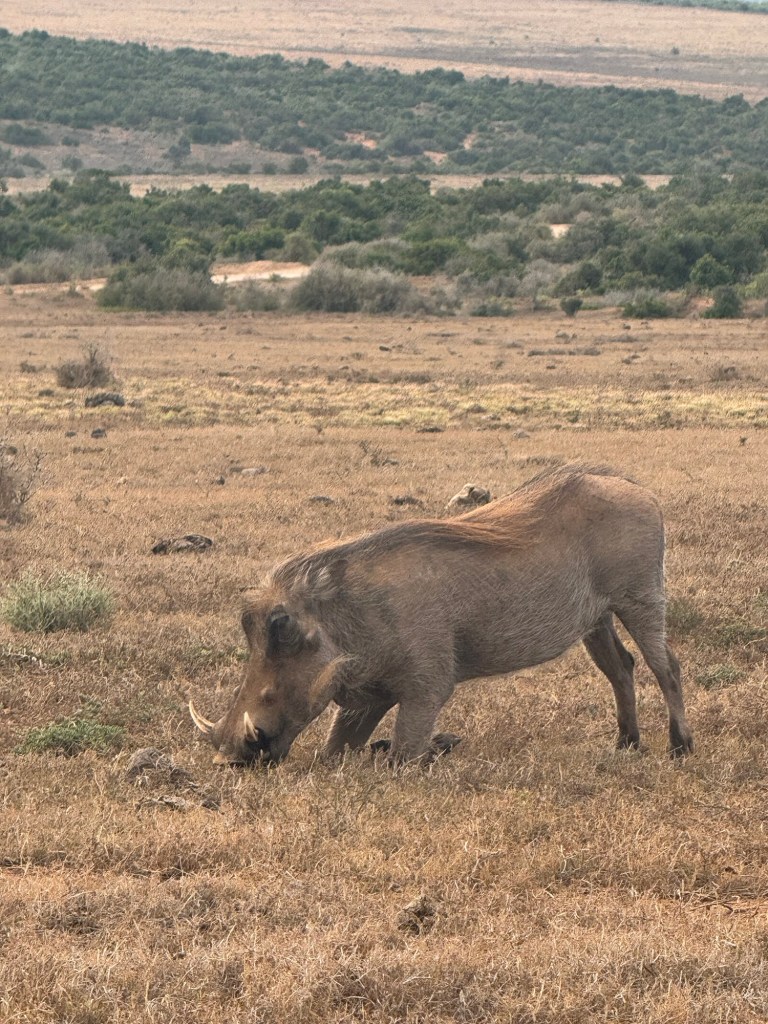

The silence of the savanna is deep. It is not the absence of sound, but a presence—something that thickens the air and slows the breath. The elephants move through it like keepers of the stillness itself, their padded feet pressing into the earth without a whisper. The herd advances as if in quiet conspiracy with the land, preserving the sanctity of morning. Then, a low rumble trembles through the herd—part command, part reassurance—and the tension fractures. Zebras wheel away from the water’s edge, warthogs back into the scrub, and white egrets scatter upward like drifting ash, their wings ghosting above the mirrored pool.

Addo Elephant National Park spreads over four hundred thousand acres across a mosaic of green-dry earth—dense coastal thicket tangled with coarse grass, fynbos clinging to wind-bitten slopes that lean toward the Karoo – a indigenous word for, ‘land of thirst’. This is elephant country: immense, yet starkly intimate. Along its ochre roads travellers trace the outlines of herds as they emerge from the bush—sometimes thirty strong, sometimes one great bull alone, immense in its quiet presence. Their only enemy is now their saviour- the one that drove them to near extinction.

A century ago, these plains—now serene—were their abattoir when European settlers discovered the fertile Sundays River Valley and the elephants became obstacles to progress. Citrus—lemons, oranges, grapefruit, clementines—rewrote the landscape and by 1920 only eleven elephants survived, the last of a persecuted lineage.

Today, their descendants roam again—joined by Kruger bulls to enrich the bloodline—while, beyond the park’s fences, citrus estates stretch to the horizon. Rows of white shade screens shimmer in the heat, guarding delicate fruit from the fierce Eastern Cape sun. The district retains its pastoral

poise: wide verandas, quiet guest houses, social clubs. Yet beneath the calm runs a more uneasy current. Many of the younger generation of ‘whites’ have drifted abroad, unwilling to compete in a government framework built to correct past wrongs. Those who remain—grey-haired stewards of family farms—live behind electrified fences and cameras.

“It’s not easy,” Gregg tells me one evening. A citrus farmer, “the white population is the same but our percentage is shrinking from ten percent of the nation to six since apartheid.” In the nearby townships the population and unemployment amongst the youth accelerates. “We do what we can for security,” he adds quietly, recalling a home invasion in 2021 when one of his relatives was shot but lived. Yet his tone carries more resolve than resignation and resonates a deep love for the land, the country and the stunning sunsets.

“I’m optimistic,” he says, “Some of the new right-wing groups are trying to work with the ANC—bring back some discipline to reduce the corruption.” He said when I asked him for a ten year forecast for South Africa. His words dissolved into the dark night. I find myself wondering what history pages will say about the fiercely proud white enclave that loves this land or will it leave blank pages for its extinction.

What great fun this must be.

From childhood through our senior years, this is the most spectacular imagining of life on Earth. Predators, grazers and bottom feeders live out the drama of the place according to patterns reaching back millions of years.

Though much more recent in tenure, we humans share the tenor of the place with something of the same zeal. Your meeting with Gregg, the Farmer, has much in common with the elephants. for example. They are a resident species here, following by at least five million years by the pachyderms, but 400 years is significant in human terms and they also think they belong. So too do the elephants, but they’re far longer adapted. Their giant feet, incongruously, are sensitive enough to perceive rain storms over 100 kms away and sets them to move toward the life sustaining water holes.

The white farmers will persist in determination a while yet, but a couple more commodity cycles and a generation from now they’ll move toward other sustaining environs, other peoples will come and go again themselves.

Looking forward to your next dispatch with appreciation.

Thanks Again, DM

LikeLike