Sir Arthur Cotton, Prawns, High Tech, Darwin, and Born-Again Christians

Andhra Pradesh, India.

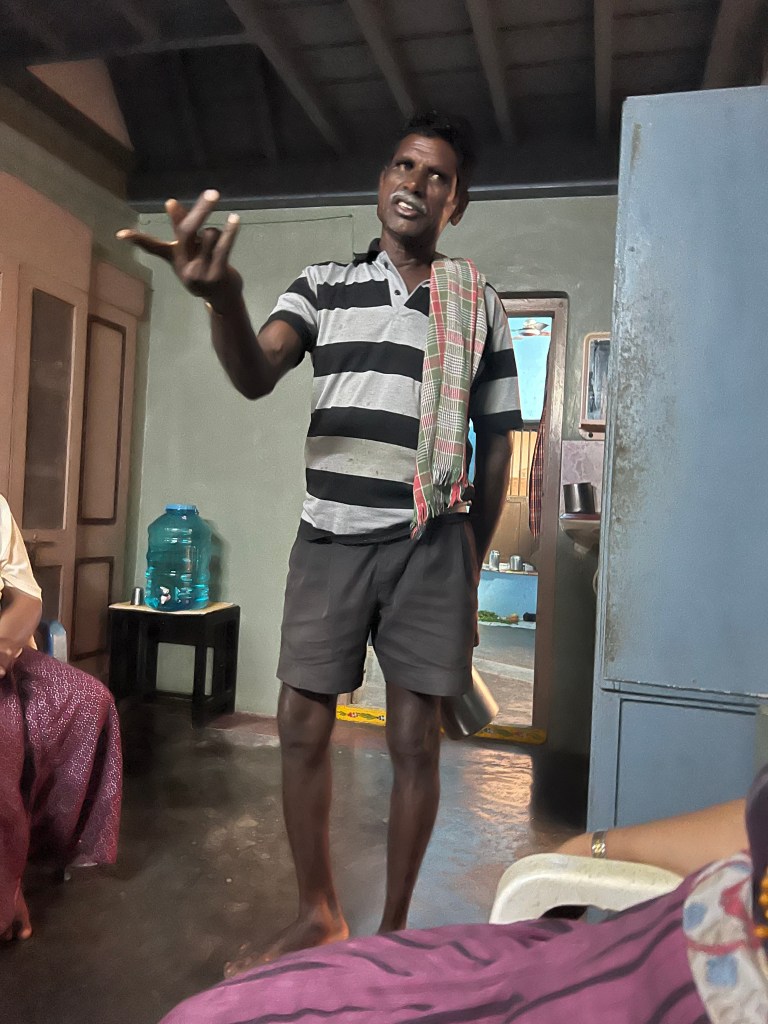

“He was not just a saint,” the farmer who lives in a stately mansion in a remote but wealthy village said to me, “He is like a god to us.” Then he waved his arm around him and added, “all of us in the state of Andhra owe everything to him. Even all of India.” His family had known wealth for three generations largely derived from farmlands transformed over decades from rice to fish and shrimp farms that stretch for miles along the canal. A canal first imagined by Sir Arthur Cotton whose statue, adorned each morning with fresh flowers, gleamed in the morning sun as women gathered to wash their clothes and men drove their waterbuffalo to lounge in its waters. He is seated regally on a horse, his back turned to the canal, and his face staring into the entrance of Aibhimavaram, one of the countless villages that made up the rice bowl of India for generations – entirely due to his vision and energy.

Despite objections from his colleagues and overlords, even under threat of impeachment, he rode through this famine prone area a hundred and eighty years before and developed a plan to harness the waters of the majestic Godavari river – the second largest in India – and build a series of interconnected canals to bring life giving water to millions of acres. Moved by famines that plagued the region, he agitated against the British plan to build railways backed by investors, instead proposing navigable waterways for commerce and irrigation. “What we have before our eyes,” he once said, “the sad and humiliating scene of magnificent (rail) Works that have cost poor India 160 million pounds, which are so utterly worthless in the respect of the first want of India, that millions are dying by the side of them.”

The Godavari – known as the “Ganges of the South” holds a mystic place in the culture as she winds across the subcontinent from the hills around Mumbai to the west and empties into the Bay of Bengal, its delta inhabited by the second highest density of population in India. It is said that deities bathed in her banks five thousand years before and even now, masses gather every 144 years for a religious festival – the Maha Pushkaran. During the last such event in 2015, politicians offered a sacred mix of cooked rice, ghee and black sesame seeds in Sir Arthur Cotton’s honour – a ritual reserved for ancestors.

Thus began the march of globalization that brings the produce of the region to dining tables all over the world. The water from the canal – unfortunately no longer as pristine as Cotton envisioned – feeds the many streams and gutters that leach through the fields into the Uppataru river that takes it back to Godavari. Instead of rice, the fields are now fish and shrimp farms producing giant prawns and Tilapia. The water also winds its way into a filtration system – setup as a non profit by a kind local businessman – that dispenses drinking water to villagers using a cashless e-comm system. Despite the hyper modern world seeping through broadband into each home, the villagers ritually invite the gods with mandalas on their doorsteps each morning.

The many mansions along the sides of the main road attest to the multigeneration wealth created, and the lush gardens, high technology penetration, and education system are testament to the vision and handiwork of one man. Vested with the capital generated, young men and women from the region flood universities and colleges worldwide and dominate the software industry globally – even producing CEOs like Satya Nadella of Microsoft, Arvind Krishna of IBM, and Santanu Narayen of Adobe Inc.

Alas there was an unintended global impact of Sir Cotton’s compassion when he retired in England in the late 1890s near Dorking, Kent, where Sir Charles Darwin would lay dying. His daughter, Lady Elizabeth Hope – a born again Christian deeply involved in the Temperance Movement – loudly proclaimed in America that she had visited Sir Charles Darwin in his death bed and he had privately recanted his theory of evolution. Although denied vehemently by Sir Darwin’s family she gave fuel to creationists – who retell her story on this day. These remote villages – an overnight train ride from the nearest international airport – where Sir Arthur Cotton is granted saint-like status has found its place to a global supply chain of rice, fish, prawns, and ideas.