“I never forget that God does everything, not me. I am not like others. They think they are doing everything.” Venkat said when I asked him how he came to own a dozen waterbuffalo when he delivered milk to my uncle in my ancestral village – an overnight train ride from Hyderabad. Each of the waterbuffalo produce 15-18 liters per day and each liter would sell for Rs. 60 or $1. At almost $500 a month he managed to run his family of four with the help of a prudent wife. His wife wove recycled bags she bartered for vegetables and was known to add water to the milk on occasion to supplement her budget.

“One of my waterbuffalo gives weak milk” he said, when questioned about the diluted milk. The householders laughed and gently scolded him but paid him, nonetheless. “next time tell your wife to go easy on the water.”

“Venkat,” I said to him, “how did you manage to acquire a dozen waterbuffalo?”

He related his entire story. His family had been making cheap indigenous alcohol – moonshine – from palm trees for so long that they had become a caste onto themselves. His father died when he was barely ten and he went to live with his aunt. He worked for her as a servant for years and watched as his cousins – her children – went to school. He is illiterate and unable to count. One day, when he was eighteen, he asked his aunt if she would pay him some money for the years of service so he could start his own life. She gave him nothing. “Didn’t I feed you all these years and allow you to sleep by the doorway?” she shouted indignantly as he walked away with his few belongings and wandered through the villages until he found work as a farm labourer.

“I saved all my money” he said, “so I could buy my own hut and even a buffalo. Then I too could find a good wife.”

Having married a clever wife his fortunes changed. He added to the herd over the years and managed to stay away from bad habits that were known to trap men in his caste: gambling and alcoholism.

“All my uncles and aunts died,” he said when I asked him if he kept in touch with the aunt that he lived with, “except her. God seems to have forgotten her.” He said without malice, “But I never went back to her house.”

“And your children,” I asked, “do they also help with the waterbuffalo?”

“No. No.” he said, his eyes opened wide, feigning shock at the suggestion, “my daughters are both bus conductors. They are 24 and 30 and earn Rs. 40k ($666.00) a month!” he said proudly, “They both finished high school” and added, “I took all their wages and bought each of them an acre of rice farm and gave them Rs. 400k each as dowry to marry good families.”

His joy was in that his daughters made more money than he. That they had more means than he. That they married boys who had better jobs than he. His pride that he had a hand in a generation turning away from wretched poverty.

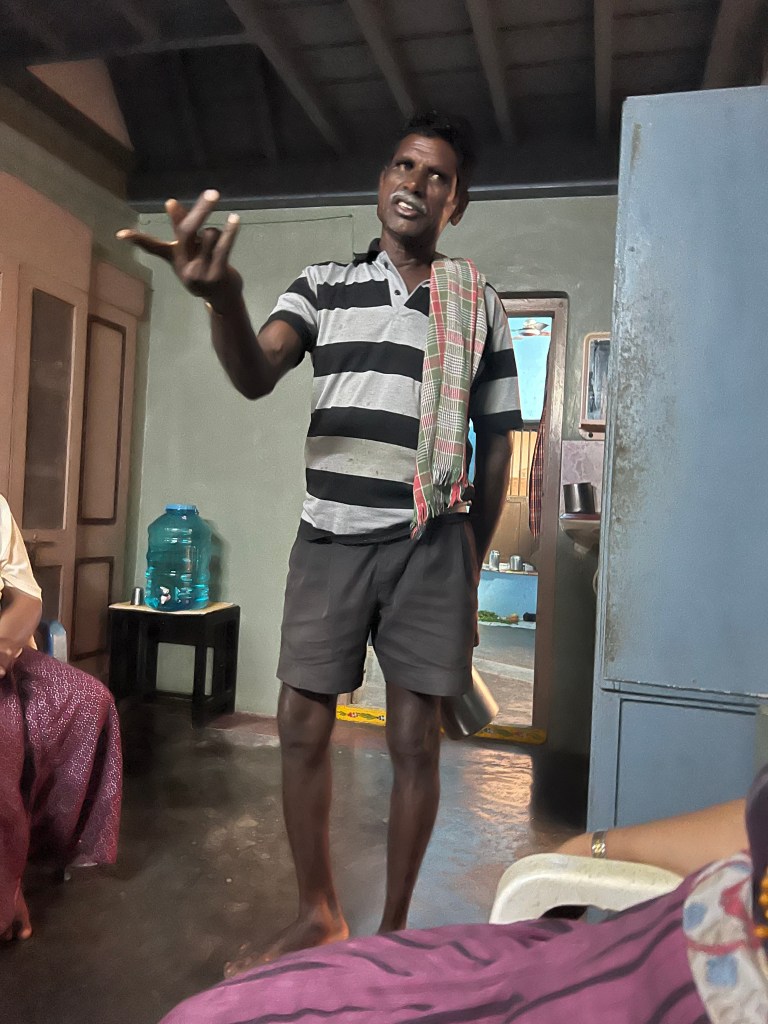

The next morning as I walked through the village, I heard his voice, “Sir,” he said in vernacular Telugu, “You are going for a walk..” I stopped and waited for him to catch up. I had never walked along the secondary street of the village that ran parallel to the main road – the wide concrete road – on which the wealthy landowners had magnificent haciendas. Unlike that street, open sewers ran along this narrow dirt road and homes were made of mud walls supported by wooden frames thatched with hand made tiles just as all homes were made in my childhood. Even today they are best suited for the heat of summer, and trapping rain water in monsoon. “I live around the corner.” he said and offered hesitantly, “will you come and see my house? I built it twenty five years ago.” “Of course,” I replied as he led me through the narrow alleys, “The whole street belongs to my people,” he said. He noticed that I was unsure what he meant, “my caste” he added.

We turned the corner near a purple church which had a colourful canopy decked in Christmas ornaments. The entire building and surrounding churchyard had lights and ornaments strung along temporary posts. “This is where the Christians live.” Venkat said and waved his arm along another alley. It was the day before Christmas. There was no school. Children rode bicycles and played games in the alleys. A motorcyclist with a enormous backpack stopped in front of us and women came out of their homes to greet him – it was the Amazon delivery man loaded with Christmas gifts. We walked past two or three small stores that sold everything from candy, cigarettes, and household items and he said casually, “they are all “kounties”” referring to the shopkeeping caste.

Eventually we came to his home. A traditional home with mud walls on wooden posts, painted white with a little disrepair showing along the edges of the windows. The front yard had a barren coconut tree, a mature Moringa Oliefera tree laden with long drumsticks reputed to be of great medicinal value, a fruit laden papaya tree and custard apple tree, an abundant guava tree and ever present hibiscus in full bloom – all testament to his wife’s handiwork.

Several waterbuffalo lay on the ground lazily chewing their cud while his mother in law pounded a stone mortar and pestle to grind curry powder. Two large, handsome roosters, trained to fight during the new year celebrations – as was traditional – had their powerful legs tied to the trees. Despite being illegal the law which rarely came to village would in any case turn a blind eye on the lunar New Years day that would occur in mid January.

“Please come in and have tea.” He said while looking at his mother in law. She continued pounding the mortar without turning her eyes. I thanked him and continued on the walk when his mother in law seemed disinclined to second his invitation. Suddenly I became aware of my posture and gait as eyes followed me through the alleys – in village India, caste is the determinant of every human encounter – after having spent most of my life in the West and much of my childhood in urban India, I realize now, that in my ancestral village, I would only be my caste and a foreigner in this street.